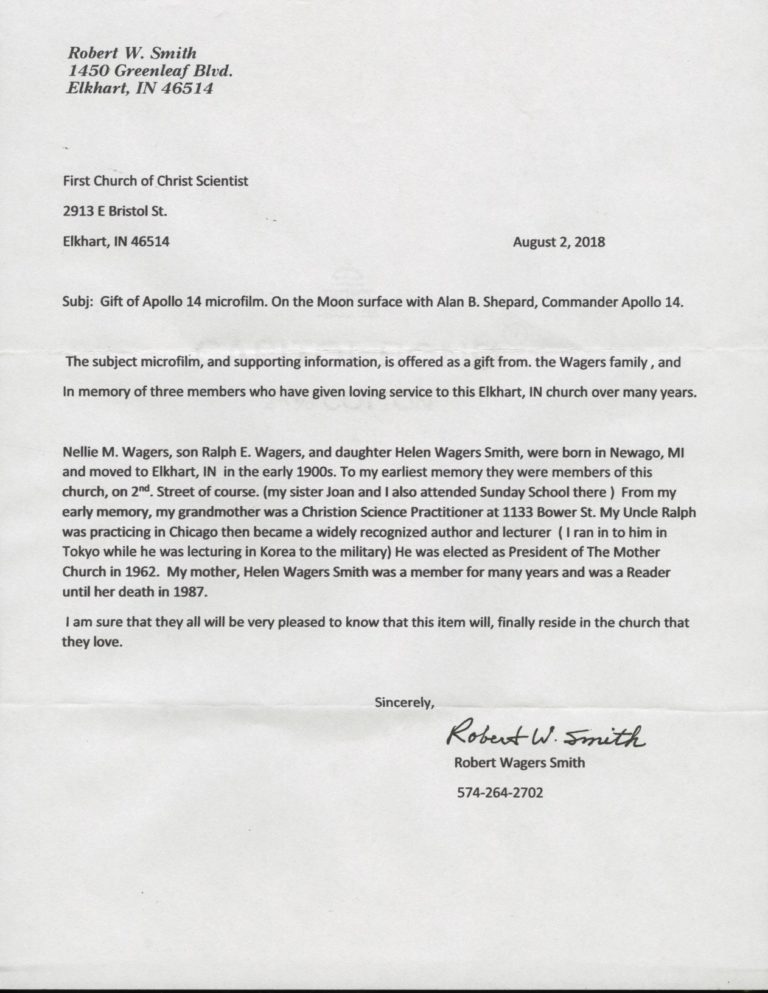

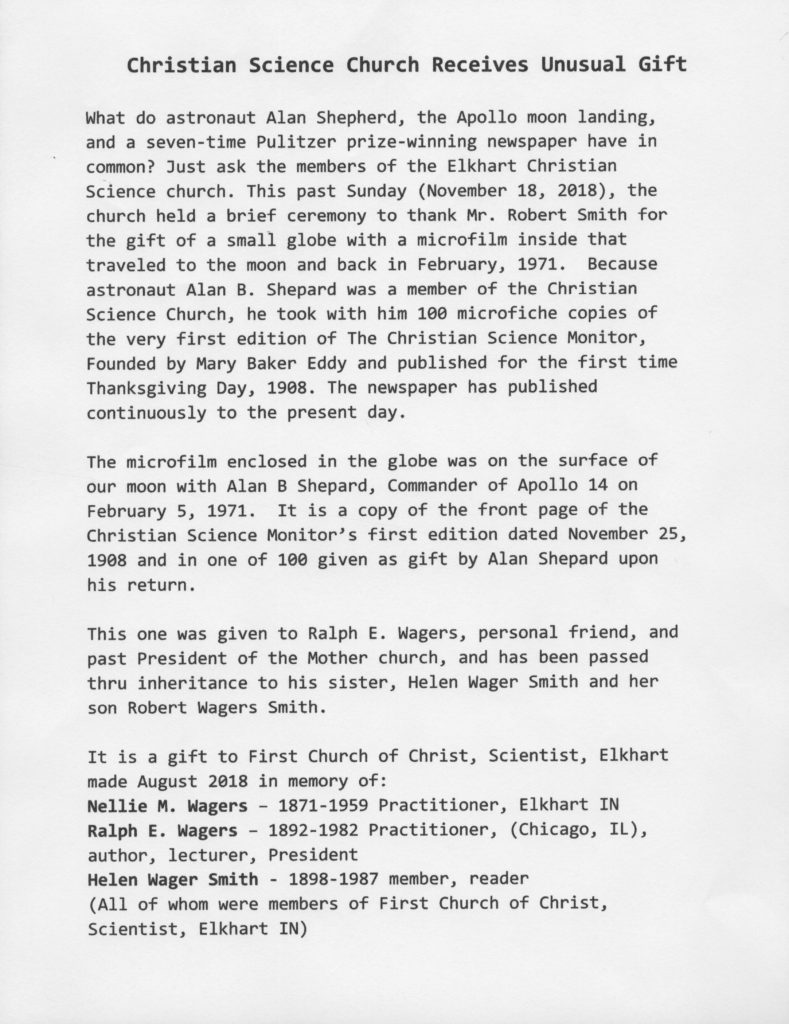

Moon Globe

Alan Shepherd Astronaut

The Mercury Seven astronauts with a USAF F-106. From left to right: M. Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Virgil I. Grissom, Walter M. Schirra, Alan B. Shepard and Donald K. Slayton.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. This shattered American confidence in its technological superiority, creating a wave of anxiety known as the Sputnik crisis. Among his responses, President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched the Space Race. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established on October 1, 1958, as a civilian agency to develop space technology. One of its first initiatives was publicly announced on December 17, 1958. This was Project Mercury,[42] which aimed to launch a man into Earth orbit, return him safely to the Earth, and evaluate his capabilities in space.[43]

NASA received permission from Eisenhower to recruit its first astronauts from the ranks of military test pilots. The service records of 508 graduates of test pilot schools were obtained from the United States Department of Defense. From these, 110 were found that matched the minimum standards:[44] the candidates had to be younger than 40, possess a bachelor’s degree or equivalent and to be 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m) or less. While these were not all strictly enforced, the height requirement was firm, owing to the size of the Project Mercury spacecraft.[45] The 110 were then split into three groups, with the most promising in the first group.[46]

The first group of 35, which included Shepard, assembled at the Pentagon on February 2, 1959. The Navy and Marine Corps officers were welcomed by the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke, while the United States Air Force officers were addressed by the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, General Thomas D. White. Both pledged their support to the Space Program, and promised that the careers of volunteers would not be adversely affected. NASA officials then briefed them on Project Mercury. They conceded that it would be a hazardous undertaking, but emphasized that it was of great national importance. That evening, Shepard discussed the day’s events with fellow naval aviators Jim Lovell, Pete Conrad and Wally Schirra, all of whom would eventually become astronauts. They were concerned about their careers, but decided to volunteer.[47][48]

The briefing process was repeated with a second group of 34 candidates a week later. Of the 69, six were found to be over the height limit, 15 were eliminated for other reasons, and 16 declined. This left NASA with 32 candidates. Since this was more than expected, NASA decided not to bother with the remaining 41 candidates, as 32 candidates seemed a more than adequate number from which to select 12 astronauts as planned. The degree of interest also indicated that far fewer would drop out during training than anticipated, which would result in training astronauts who would not be required to fly Project Mercury missions. It was therefore decided to cut the number of astronauts selected to just six.[49] Then came a grueling series of physical and psychological tests at the Lovelace Clinic and the Wright Aerospace Medical Laboratory.[50] Only one candidate, Lovell, was eliminated on medical grounds at this stage, and the diagnosis was later found to be in error;[51] thirteen others were recommended with reservations. The director of the NASA Space Task Group, Robert R. Gilruth, found himself unable to select only six from the remaining eighteen, and ultimately seven were chosen.[51]

Shepard was informed of his selection on April 1, 1959. Two days later he traveled to Boston with Louise for the wedding of his cousin Anne, and was able to break the news to his parents and sister.[52][53] The identities of the seven were announced at a press conference at Dolley Madison House in Washington, D.C., on April 9, 1959:[54] Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton.[55] The magnitude of the challenge ahead of them was made clear a few weeks later, on the night of May 18, 1959, when the seven astronauts gathered at Cape Canaveral to watch their first rocket launch, of an SM-65D Atlas, which was similar to the one that was to carry them into orbit. A few minutes after liftoff, it spectacularly exploded, lighting up the night sky. The astronauts were stunned. Shepard turned to Glenn and said: “Well, I’m glad they got that out of the way.”